Días de Lava: del sueño de niñez a la ciencia / Lava days: from childhood dream to the science

This post is from Ivan Torres a PhD student at the University of Missouri Kansas City who joined the MELT team from Chile in January 2022. She has written the post in Spanish (Top) and English (Bottom). This blog has always been about bringing science to more people, and Ivana's language skills will help us do expand this effort!

Días de Lava: del sueño de niñez a la ciencia

Desde que entré a este mundo de re-fundir lava

sobre los 1300°C, he estado subiendo contenido a las redes sociales (imágenes y

videos) de algunos de los experimentos que realizamos en nuestros laboratorios

en University of Missouri-Kansas (UMKC) y en las facilidades de University of

Buffalo (UB). Y adivinen cuál ha sido el comentario más común en estos videos… “¡MI SUEÑO DE NIÑEZ ERA JUGAR CON LAVA!”.

Pasando del hecho que trabajar con roca líquida

es uno de los sueños de niñez más peligroso, lo que realmente hacemos en

nuestros experimentos (además, de pasarlo bien y tener videos muy entretenidos)

es entender cómo el calor se transmite desde la roca líquida al sedimento.

Sé lo que estás pensando: “wooow, espera un

poco, nos movimos muy rápido del sueño de niñez a la ciencia”, así que déjame

explicarte cómo mi experimento soñado desarrolló un perfil científico.

Para nuestro propósito científico, utilizamos

sensores de temperatura (llamados termopares) y de humedad (del tipo TDR100 y

capacitivos). ¿Qué significa esto? significa que estos sensores leen y escriben

en una memoria, los cambios de temperatura y humedad en el sedimento luego de

que hemos vertido la roca líquida (¿sabían que la humedad dentro del sedimento

no es humidity sino moisture en inglés?)

De los sensores de temperatura y humedad

recolectamos muchos datos en tan solo un experimento, (ej: si nuestro

experimento es de una hora, tenemos al menos 3600 datos por sensor). Hemos aprendido

cómo colectar datos en los experimentos a gran escala, gracias a los

experimentos de pequeña escala que realizamos en UMKC.

Entonces, ¿Qué es un experimento a pequeña o gran escala?, los experimentos de pequeña escala son aquellos en los cuales sólo usamos 6 mililitros de roca líquida y al menos 3 kilogramos de sedimento (pequeño, ¿cierto?), pero, ir a lo GRANDE (gran escala) involucra litros y litros (y litros) de roca líquida (30 litros aproximadamente) y kilogramo tras kilogramo de sedimento, para crear nuestros pequeños volcanes (comparados con los reales).

Para una mejor comprensión mira algunos videos

un poco más abajo, y así puedes sacar tus propias conclusiones de que es grande

o pequeño.

En nuestros experimentos de pequeña escala (en

UMKC), usamos los sensores de temperatura distribuidos verticalmente en

distintos sedimentos (arena y grava) para ver cómo el calor es transferido

hacia abajo desde el punto de contacto entre la roca líquida y el sedimento.

Esto nos ayuda a tomar mejores decisiones para la ubicación perfecta de los

sensores cuando queremos ir a A LO GRANDE!

Experimentos a gran escala en las Facilidades de UB.

Y, ¿qué rol juegan los sensores de humedad?

Bueno, usamos dos tipos de sensores en nuestros

experimentos a gran escala, TDR100 y sensores capacitivos. Ambos colectan datos

de formas distintas, pero su funcionamiento será explicado en una futura

publicación (no queremos hacer que tu cabeza explote con tanta información, al

menos por ahora…). La importancia de ellos radica en saber el contenido de agua

disponible en el sedimento cuando vertemos nuestra roca líquida. Pero ¿por qué

nos interesa saber esto? porque la presencia de agua puede cambiar la manera en

que la lava o el magma interactúan. En el caso de los experimentos, el

contenido de agua afecta en cómo la temperatura es transferida al sedimento.

Además, la presencia de agua provoca diferentes reacciones debido a la

interacción con el magma, t

Enfoquémonos un poco en las peperitas y su importancia en este proyecto. ¿Qué son las peperitas? Por definición, las peperitas son una roca volcano-sedimentaria que se forma cuando el magma intruye sedimentos húmedos e inconsolidados, mezclándose y creando una roca con magma suspendido en sedimento (White, 2002).

Una vez finalizada la recolección de datos termales

y de humedad, los pequeños volcanes son destruidos para recolectar la evidencia

física de la interacción entre la roca liquida y el sedimento (como peperitas

experimentales). Esta es la forma más fácil de comparar nuestros resultados

experimentales con los depósitos naturales de erupciones previas en la Tierra.

¿Por qué investigamos estas interacciones?

Sabemos que estas interacciones ocurren en la

naturaleza, pero necesitamos saber cuándo y especificar cómo ocurre. ¿Cuánta

agua necesitamos?, ¿cuán caliente debe estar nuestra roca líquida?, ¿qué tan

rápido la roca líquida debe moverse?, y otras tantas preguntas sobre las

condiciones específicas que gatillan diferentes respuestas de la interacción

del magma/lava en sedimentos.

Es por esto, que todo un proyecto financiado

por la Fundación Nacional de Ciencia (NSF en inglés) que incluye múltiples

científicos de diferentes grados, Dra. Alison Graettinger, Dra. Susan Sakimoto,

Dr. Ingo Sonder, PhD: Ivana Torres y estudiantes de pregrado Tabitha Tyler y

Ramiro Flores, trabajan juntos para resolver algunas de estas preguntas.

Así que sí, nuestro sueño de niñez puede ayudar

a volcanólogos a entender comportamientos de volcanes, ¿loco, verdad?

Seguiremos subiendo información de cada etapa

de nuestros futuros experimentos, ¡así que no pierdas este blog de vista porque

todas esas palabras raras que hoy leíste mañana serán conocimiento en tu

cabeza!

----------------------------------

Lava days: from childhood dream to

the science

Since I entered the world of experimenting with remelted lava at temperatures up to 1300°C (~2500 F) I’ve been posting to social media images and videos of some experiments that we run in our lab at the University of Missouri-Kansas City (UMKC) and at the University at Buffalo (UB) facilities. And guess what was the most common reply to the videos? “MY CHILDHOOD DREAM WAS PLAYING WITH LAVA!”

Beyond the fact that working with molten rock is one of the most dangerous childhood dreams, what we aim to do in our experiments (besides have a fun time and make great videos) is understand how the heat from the molten rock is transmitted to the sediment.

I know what you are thinking: “Wow,

wait a little bit, we moved too fast from the childhood dream to the science”,

so let me explain how my dream experiment develops a scientific view.

For our scientific purpose we use

sensors, temperature (called thermocouples) and moisture sensor (TDR100 and

Capacitive type) to measure the experiments. But what does that mean? These sensors

read and write (in a datalogger) the changes of the temperature and moisture

(or how non-English speakers love to say: humidity) in the sediment after we

pour molten rock on it during our experiments.

With the temperature and moisture

sensors we collect many datapoints from one experiment (if our experiment takes

1 hour, we have at least 3600 data per sensor!!). We have been learning how to

collect more data in the big-scale experiments, thanks to the small-scale

experiment that we do at UMKC.

Wait, What is small scale

experiment and a big scale experiment? In the small scale experiment we just use

6 milliliters (0,001 gallons) of melt

and at least 3 kilograms of sediment (small, right?). But, go BIG involves

liters and liters (and liters) of melt (30 L or 8 gallons) and kilograms and kilograms of sediment to

create our little volcanoes (little compared with the real ones). For a better

understanding take a look at some videos, so you can make your own conclusion

about what is big or small.

See video links above.

In our small-scale experiments (at UMKC), we use thermocouples vertically distributed in different types of sediments (sand and gravel) to see how the heat is transferred downward from the point of contact between the melt and the sediment to the bottom part of it. This helps us to make better decisions for the perfect location in the sensor when we want to go BIG!

What about the moisture sensors?

Well, we use two types of moisture sensors in our big-scale experiments, TDR100 and Capacitive moisture sensor. Both works in different ways and the differences between them will be explained in a future post (we don’t want to blow your mind with so much information. At least for now…). The importance of them is to know the water available in the sediments when we are pouring melt. But why? Because the presence of water can change the way lava or magma behaves and, for the experiments, how the temperature is transferred to sediments. Besides, many different reactions can be triggered form from water and magma interacting, this include textures as pillow lavas, explosive interactions, or complex rocks like peperites.

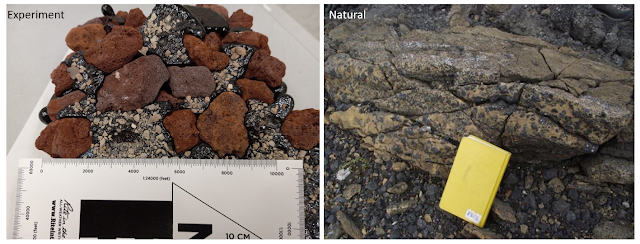

Let’s focus a little bit on the peperite and the importance for this project. So first, what is a peperite? By definition, is a volcaniclastic rock, formed when the magma intrudes unconsolidated wet sediment and mingles making a rock with bits of magma suspended in sediment (White, 2000). You can see in the pictures above the mixture of melt in sediment.

Once we finish recording all the thermal and moisture data for our experiment, we destroy our little volcanoes to see physically how the melt interact with the sediment. This part is the easiest way to compare with the natural records for previous eruptions on the Earth.

Why we research these interactions?

We know that this happen in the nature but we need to know when and the specifics of how it happens. How much water do we need? How hot does the melt have to be? How fast does the melt have to move? And so many other questions on the specific conditions that cause the different responses of magma/lava sediment, and that is why an entire project funding by the National Science Foundation that include multiple scientists from different degrees (Dr. Alison Graettinger, Dr. Susan Sakimoto, Dr. Ingo Sonder, PhD student: Ivana Torres, Undergraduate students: Tabitha Tyler and Ramiro Flores) join together to give answer for some of these questions, running fun experiments with lava in our lava days!

Wow so our childhood dream is the beginning of a scientific investigation to understand real behavior of volcanoes in the nature, wild right?

We are going to keep giving you more information about the experiment and volcanoes (YAAY) so don’t lose sight this blog, because all those specialty words that you read today will be knowledge tomorrow!

See you soon!